By Matt Marble

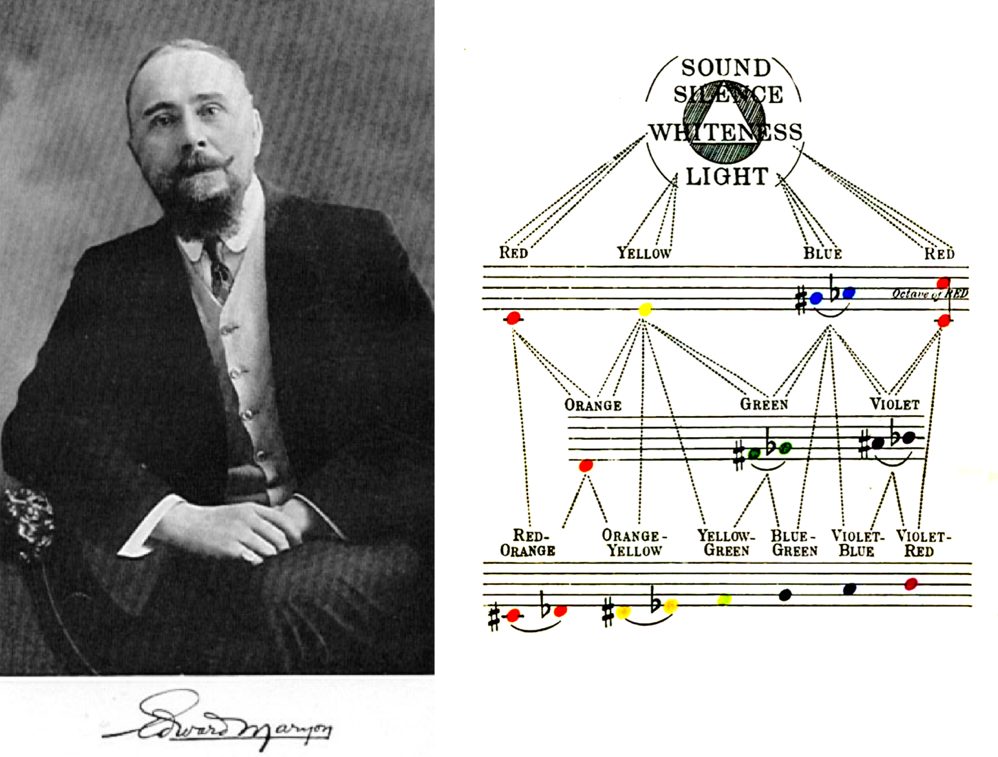

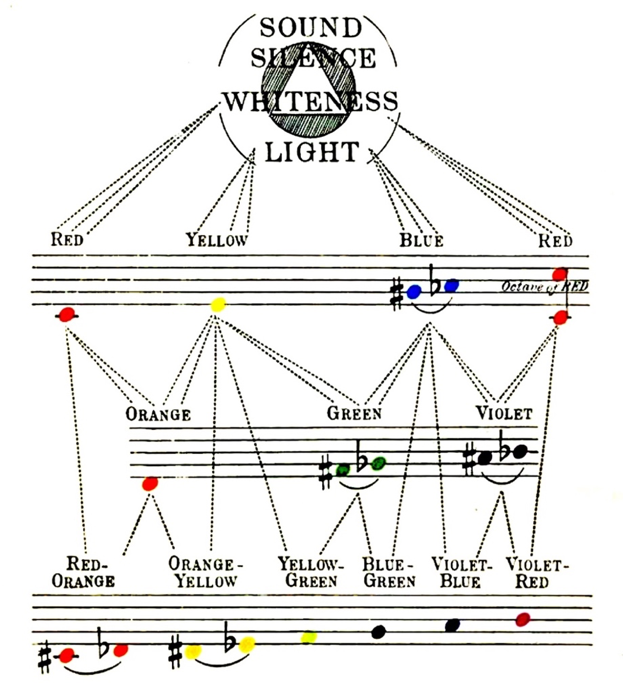

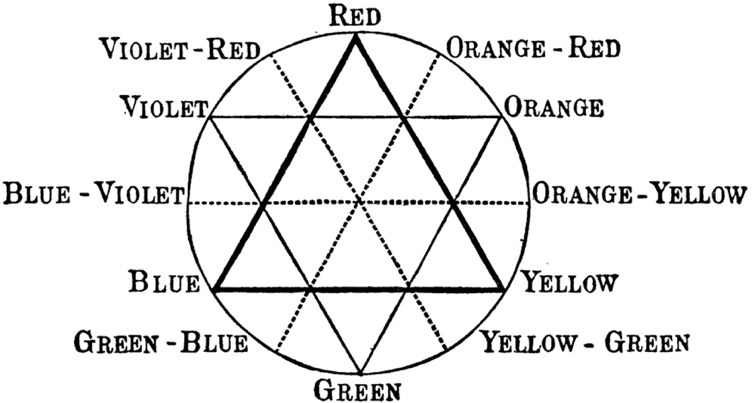

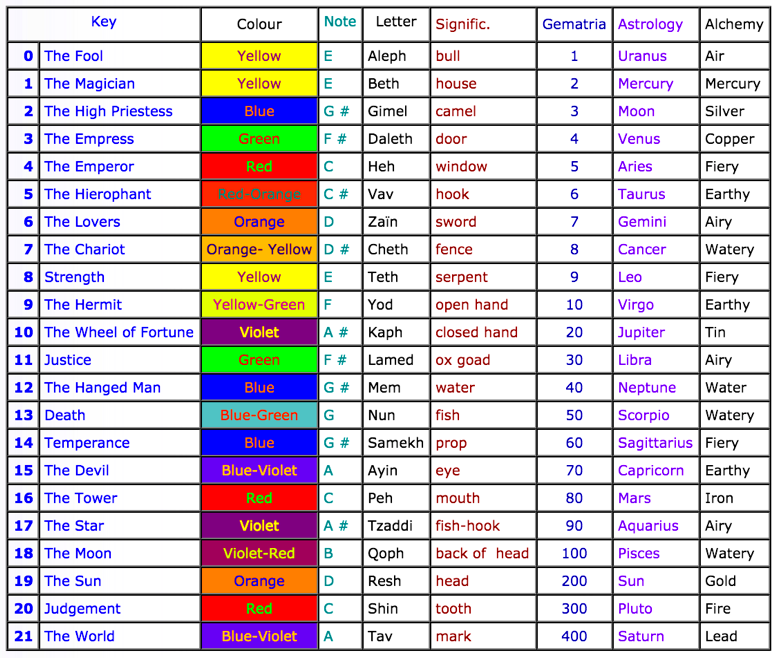

Right, the tone-color correspondences of Marcotone theory

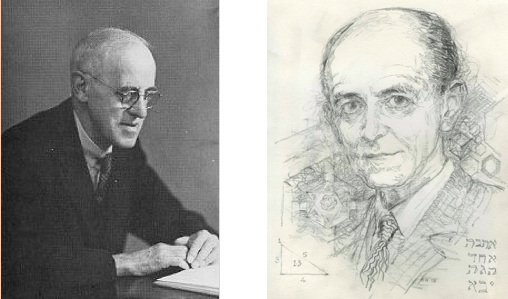

Throughout his life, both in America and Europe, John Edward Daulby (1867-1954) wanted nothing more than to be a composer. But in pursuit of this aim he wandered down some strange paths—secret societies, esoteric science, false aristocratic titles, world travel and lavish living, as well as art counterfeiting and imprisonment. Daulby [as I will refer to him throughout this essay] is almost forgotten to us today. A curious few may know of him by his pseudonym as Edward Maryon. Maryon is known as an esoteric philosopher/composer and the author of Marcotone: The Science of Tone Color (1915), a mnemonic music method based on tone-color correspondences. But there seemed to be scarce information on Daulby beyond Marcotone.

Curious to know more, I dove into late 19th and early 20th century newspapers, magazines, memoires, and related documents. In doing so I found much more than I expected, including over a dozen different personas and aliases—all of which I sourced back to a John Edward Daulby, the son of a tailor from Essex, England. I have reduced Daulby’s catalogue of identities to four main branches.

I. There was Edward Maryon the composer, esoteric philosopher, educator, and author of Marcotone, Daulby’s “tone-color science.” This would be Daulby’s most enduring name.

II. There was Grand Master of the Order of Mélusine and Prince de Lusignan. Daulby would rise in the ranks of the Order of Mélusine, an esoteric French secret society that worshipped a mythical mermaid and appropriated Anglo-Saxon ancestry.

III. There was Count d’Aulby de Gatigny and Prince del Borghetto, royal names Daulby appropriated by the dubious purchase of property or by personal affiliation. Daulby lived lavishly under these personas.

IV. Then there was J.E. Maryon-Daulby, the art dealer, who also went by Count Daulby. Daulby began selling paintings in the 1880s, but by 1910 was arrested for selling fake masterworks to a wealthy Duchess.

Realizing that there was no single writing available connecting all these personas, I dove into Daulby’s writings and news archives. Gradually, as I began connecting the dots, a unified portrait of Daulby took shape. As one New York Times journalist put it, Daulby is “a character who would have adorned the pages of Dickens or Gaboriau” (“D’aulby Protégé”).

Below is a list of some of Daulby’s names and titles. Newspapers, however, would often variably misspell his names. I have retained the most consistent names in my own writing; and when quoting periodicals, I have retained their original spellings.

John Edward Daulby Count d’Aulby de Gatigny

“Jack” Daulby George Daulby

J.E. Maryon-Daulby Charles Edward d’Aulby

Edward Maryon Edward Maryon d’Aulby

Comte Jean Eduard d’Aulby Prince de Lusignan

Prince del Borghetto Prince de Montecompatri and Monteportium

Edward Maryon: Composer

Above all possibility of concrete thought, the Tone-poet Seer reveals to us the Inexpressible: we divine, nay, feel and see that this insistent World of Will is also but a state that vanishes before the One: “I know that my Redeemer liveth!”

Richard Wagner

Daulby was born in the parish of Braintree, in Essex, England on April 3, 1867. His father, John Edward Daulby, Sr., was a well regarded tailor and his mother a non-professional singer and pianist. Daulby’s attraction to music began at an early age. Known to his childhood friends as “Jack” Daulby, he began learning the piano at age 5 and the organ at age 8. He was said to have practiced the piano for 8 hours a day as a child. At the age of 14 he was organist of the Rayne and Braintree parish churches. Three years later Daulby began study at the Royal Academy of Music in London (1885-1887), where he studied piano with Oscar Beringer and composition with Ebenezer Prout and Sir George Macfarren.

At the age of 19, Daulby moved to Paris, in large part to study the work of Chopin with I. Libich, said to be a pupil of Chopin (Hipschcr). His music was well received across Europe, especially in Paris. And in 1890 he was awarded a gold medal and the “Grand Prix” award from the French Republic for his opera, L’Odalisque. Daulby was also elected as a member of the Academy of Arts (Rome) and the Society of Arts (London), among numerous other honorary degrees and decorations.

Daulby then moved to Dresden, where he lived for 18 months. There, he studied music with Max von Pauer and Franz Wullner in Cologne—Wullner had premiered Wagner’s operas. While in Cologne Daulby also became the City Chapel master. He seems to have left an impression everywhere he went. From 1890 to 1910, he garnered awards, reviews, and professional opportunities.

Daulby’s music was generally of epic proportions with esoteric, mythic, and orientalist symbolism. He primarily composed operas and other large scale works. He aesthetically revered Frederic Chopin and Richard Wagner. Wagner in particular was Daulby’s hero and model. For Wagner was the self-identified “poet priest” seeking a “musical clairvoyance” that tapped the listener into “currents of Divine Thought.” And in operas like Tristan und Isolde, Parsifal, and The Ring, Wagner reflected an idiosyncratic spiritual philosophy, one which curiously foreshadowed the Theosophical philosophy of Madame Blavatsky. Beyond regional German legend and the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, Wagner also studied “the two sublimest of religions, Brahminism with its offshoot Buddhism, and Christianity”—though with an emphasis upon Christianity (Wagner). Theosophy instantly held up Wagner as a model of Theosophical thought and art. In 1896 Theosophist Basil Crump wrote:

Art has ever been one of the moral teachers of humanity and its highest function is probably the drama as presented to us in this century by Richard Wagner, in whose extraordinary genius we find the most wonderful combination of arts that is known to history. He was a poet, musician and dramatist of the highest order, and in his prose works he bases all his theories on principles which are practically identical with those of Theosophy (Crump).

Wagner’s spiritually infused multi-media concept of gesamptkunstwerk was used to describe “the noblest expression of the people’s consciousness,” inspiring many composers to take seriously theatrical and operatic form. Noting Tristan und Isolde as Wagner’s most “perfect” composition, Daulby praises the nationalism of sources in Wagner’s works, those native legends of the Wartbürg, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin in Germany. Like other visionary composers of the early 20th century—e.g. Arthur Farwell, Francis Grierson—Daulby was inspired by Wagner’s radical and holistic re-conception of art, spirituality, and humanity. This wasn’t just music, but a divinely inspired effort to spiritually evolve mankind.

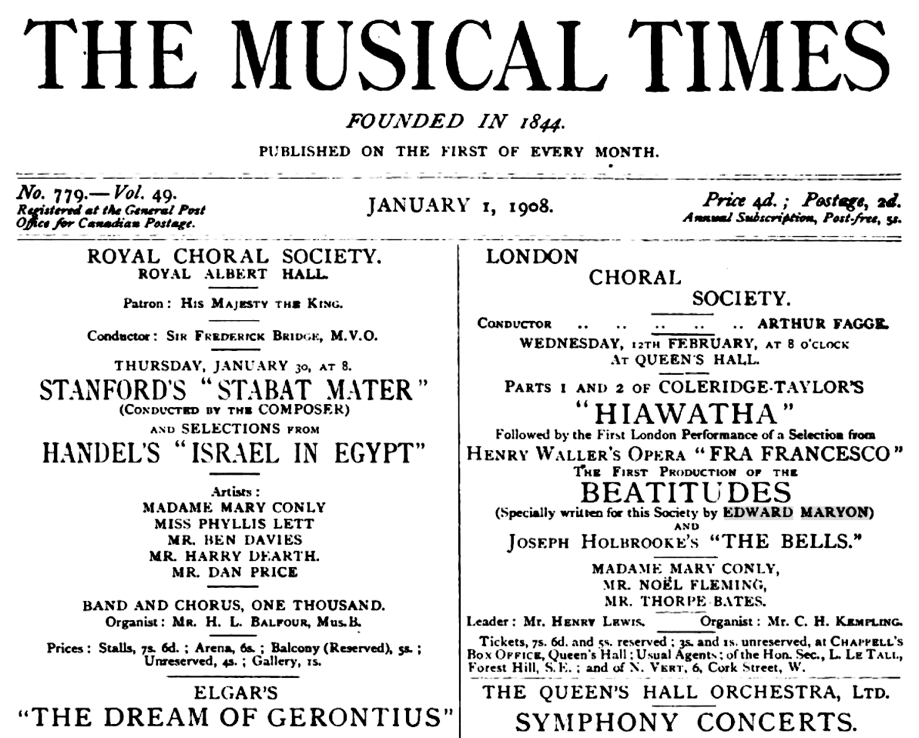

Almost 20 years after L’Odalisque, Daulby’s next most notable work was his sacred cantata, Beatitudes (1908). Referring to the blessings compiled by Jesus Christ in his Sermon on the Mount (Matthew, 5:3-11), Daulby set this Biblical text for solo baritone singer, double chorus, orchestra, and organ. Though there are no recordings by which to hear Daulby’s music today, news reviews of the time give us an idea of what his Wagnerian music sounded like. Beatitudes achieved international news coverage.

“Maryon was a highly skilled technician,” writes one reviewer. “His orchestral scores are complex, precise, and somewhat revolutionary; they prove a technical mastery suggestive of Richard Wagner” (Johnson). Though he was also dealt his fair share of negative reviews. Regarding Beatitudes, one reviewer writes, “There are many signs of weakness, not only in the general plan, but in the composition and orchestration, whilst the whole is too rhapsodical and flamboyant” (Musical News).

A later work, Chrysalis, is a “lyric mystery-play in two acts” depicting the loss of love and mystical transformation. The work had its premiere in 1929 at the Freiburg Opera in Germany. “Its story deals with the grievings of a young man for the death of his beloved in an aeroplane accident, until, through the mystic power of a chrysalis [or, insect pupa] from the Far East, he is transformed to a plane of doubt and irreality, and his dozen-years-dead betrothed returns and calls him to their reunion” (Hipschr).

In the four-act opera, Werewolf, Daulby devised a symbolic compositional process by which the human persona was associated with the diatonic scale, and the lupine by the whole-tone scale. In fact, throughout his operas he expressed a fixation on the whole-tone scale.

An earlier one-act opera from 1905, La Robe de Plume (The Feathered Robe), was inspired by a Shinto legend from Fujiyama, Japan. Still other works reference Ancient Greek and Egyptian myths, Medieval legends and mystery-plays, or Biblical and Theosophical symbolism, often with large instrumental forces.

L’Odalisque (1890), Daulby’s first opera

La Robe de Plume, The Feathered Robe (1905), one-act opera based on a Shinto legend from Fujiyama

Beatitudes (1908), sacred cantata for solo baritone, double chorus, orchestra, and organ

Sphinx (1916), tone-poem for baritone solo and orchestra

A Lover’s Tale, an operatic World War version of Dante’s “Paolo and Francesca” in one act

The Call of Jeanne d’Arc (1923), one-act opera on Percy MacKaye’s “Joan of Arc”

Eight Hundred Rubles (1926), one-act grand opera, libretto by John G. Neidhardt

Chrysalis (1929), two-act lyric mystery-play

The Smelting Pot, three-act American opera dedicated to Walt Whitman

Rip van Winkle, American ballet

Werewolf, four-act American opera dedicated to Edgar Allen Poe

Armageddon Requiem, for solo voices, triple chorus, and orchestra

The Cycle of Life, operatic heptalogy

The Prodigal Son

Rembrandt

A Golden Shower, or Danae

Greater Love

Abelard and Heloise

Both in America and in Europe, Daulby would continue composing operas into the late 1920s, and likely beyond. Like Wagner, Daulby’s art was extra-musical, guided by and expressing a spiritual perspective and prophetic imperatives. Driving Daulby’s music was his devout esoteric beliefs inspired by Theosophy, Baha’ism, Vedantic Hinduism, Jewish Kabbalah, as well as Anglo Saxon myth and legend. Through these lenses Daulby felt his music could be a catalyst for the social and spiritual evolution of humanity. Daulby’s The Cycle of Life, 40 years in the making would lay out his esoteric perspective in great detail.

Edward Maryon: Esoteric Philosopher

Is not Man’s truest expression in song? Are not all the suns of all the Universes qualified by the power of their chantings?

The disciple of the Ancient Wisdom must become the student of Modern Music, and the musician must become the student of the Ancient Wisdom, if both would realize their divine powers to the utmost; for Music and Morals are esoterically inseparable.

Edward Maryon (1907)

Daulby’s interest in esoteric traditions began around the turn of the century, when Theosophy, Spiritualism, and the Baha’i faith were in the foreground of the cultural zeitgeist. But he seemed to explore and make connections with all manner of esotericism. It was in Paris that he would meet the grand master and maîtres of the Order of Mélusine, to which he would become heir in 1885. With this mythological couple Daulby embraced an esoteric initiatory society while mingling with high society. The heraldic myths and symbolic drama of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon traditions would infuse Daulby’s music. We’ll look into this secret society more later.

Also while in Paris, Daulby studied privately with Dr. Carl Hansen in the fields of “archaic languages, psychics, and esoteric philosophies.” Hansen is still considered the “father of modern hypnotism” and was an internationally well known stage hypnotist. His performances—seen by the likes of Sigmund Freud—engaged in “preposterous pantomimes, standing up and singing, eating a raw potato believing it to be a pear; and drinking imaginary champagne from real glasses and thereafter behaving as if intoxicated” (Crary). Little else is known of Daulby’s relations with Hansen, but Daulby was likely an ardent believer, or at the very least he was impressed with Hansen’s esoteric theatrics.

I found another esoteric French connection that would remain with Daulby throughout his life. Daulby’s largest work, The Cycle of Life, was apparently “warmly encouraged” over the course of 46 years by French esoteric philosopher Edouard Schuré, who was, notably, a friend to Richard Wagner, Rudolph Steiner, and Frederick Nietzsche (Musical Times). Schuré himself began staging esoteric dramas in 1908. He wrote and published regularly on musical and esoteric topics, and is most known for his book The Great Initiates (1889). Schuré’s writings on Wagner and multi-cultural esoteric perspectives (e.g. Krishna and Orpheus, 1908; From Sphinx to Christ, 1912) were, I assume, influential or inspiring to Daulby (Musical Times).

But Daulby’s esoteric perspective was largely shaped by the philosophy of the Theosophical Society, founded by Madame H.P. Blavatsky in 1875. Daulby likely would have followed Theosophy before the turn of the century. In 1905 Daulby wrote the article, “The Theosophical Society and Music,” for the Theosophical Journal. Here he proclaims the spiritual and social duties of music as well as the importance of regional myth, race, and nationalism. He proclaims his seven-act opera, The Cycle of Life, to be a means of nationalist solidarity and mankind’s spiritual evolution. Begun as early as 1886, Daulby would work on The Cycle of Life for decades. This work, a heptalogy, consisted of seven “mystical dramas”—Lucifer, Cain, Krishna, Magdalen, Sangraal, Psyche, and Nirvana.

“Lucifer” is a view of the advent of all formative life, suns, planets, and creatures. “Cain” treats of the union of the third and fourth races on our planet and the attainment of the soul. “Krishna” is concerned with the rise of the sixth race, ours, the Aryan, and the attainment of wisdom in a universal philosophy, the Vedanta. “Magdalen” is the union of the Hermetic, Henochian, and Hellenic philosophies, into humanitarian ethics, through the Syrian incarnation, “Christos.”

“Sangraal (Christos)” is the blending of the religious with romanticism, according to Le Morte d’Arthur [1485] of [Thomas] Mallory. “Psyche” brings this cosmical record to our own time. It deals with the World War and exposes the psychic, or astral, and the spiritual planes. “Nirvana” furnishes a picture of Space-Time how all form is transmuted and finally is in union with the absolute Unity, God (Hipschr).

In Theosophical manner, Daulby fuses the mythology and esoteric traditions of India, Chaldea, Egypt, and Greece. And in the description above we meet a host of Theosophical concepts: cosmic consciousness, root races, astral planes, Vedantic deities. The overriding esoteric perspective is the “universal philosophy” of Indian Vedanta. However, Daulby’s understanding of Vedanta was likely thoroughly informed by the Theosophical interpretation of Madame H.P. Blavatsky.

Let us focus on the fourth movement “Sangraal (Christos),” which in Daulby’s Theosophical essay he called “the first stone” upon which “to raise our National Art.” In 1891 Blavatsky described Christos as, “the union of man with the divine principle in him. As Paul says, ‘That you may find Christos in your inner man through knowledge.’” In prophetic language Blavatsky reflects upon the “coming down upon the Earth of the Spirit of Truth (Christos), after which advent—that has once more naught to do with Jesus—will begin the Golden Age.” Emphasizing the pre-Christian origin of the term, Christos is not Jesus Christ but, rather, “that blessed condition of inner theophany,” the divined self of the here and now.

“Sangraal” expresses Daulby’s artistic philosophy as “a blending of the religious with romanticism.” He takes Blavatsky’s concept of Christos, the divine role of the artist, and clothes it with English myth and legend. Referring to the legend of King Arthur, the medieval term sangréal (or sangraal) means “holy grail.” A romantic history based upon the legends of King Arthur—amongst a multi-cultural esoteric mash-up—then became the backdrop of Daulby’s musical landscape.

The Cycle of Life’s seven movements, each its own “music-drama,” likely reflect Theosophy’s reverence for the number “7,” and in particular the seven cosmic rays at the core of its philosophy—though that tradition, notably, often deferred ascribing colors to the seven rays. Daulby proclaimed each movement of The Cycle of Life to be “a rock on which to raise our National Art, even to that highest pinnacle to which our native genius may aspire.” In most references to this work it appears that only a few movements were ever performed, and that the work as a whole was unfinished. However, I was able to find one note that indicated Daulby’s Cycle of Life may have received a performance, or an attempt at one, by composer, conductor, and music writer Nicholas Slonimsky. By the 1950s Daulby’s publishers assumed he was dead. “After a futile appeal to Scotland Yard,” Slonimsky says that he “discovered [Daulby] alive in London.” Before he died, Daulby left “all his manuscripts” with Slonimsky (Luce).

Daulby’s writings on music and the imagery used in his operas also reflect the philosophy of the Baha’i faith, the monotheistic Persian religion of social and religious unity, founded by Baha’u’llah in 1863. Daulby was especially drawn to the allegorical mythology of Baha’i. Symbolic Baha’i figures, such as the Holy Mariner and the Maid of Heaven, were included in his heptalogy. In a 1921 essay called “Marcotone”—published in the Baha’i magazine, Reality—Daulby champions the Baha’i faith. “If Baha’ism symbolizes its ideals the Unity of Men, the Unity of Humanity, it is the At-one-ment or union with God. If this is indeed so, it justifies these “Words of Wisdom” taught us by Baha’u’llah:

“Its Light (Light of the Sun of Truth) when cast on the mirrors of the wise gives expression to wisdom; when reflected from the minds of artists it produces manifestations of new and beautiful arts; when it shines through the minds of students it reveals knowledge and unfolds mysteries.”

Daulby’s music, lecturing, and writing were reverentially received by the Baha’i community. As the editor of Reality magazine appended to Daulby’s essay:

Edward Maryon belongs to the New Day, the Day of the complete realization of the beauty of life and the privilege of understanding and enjoying this beauty. In his remarkable discovery of the relation between color and music, he is but another example of the work of that unseen force ever seeking to enlighten man as to the possibilities and privileges he possesses on this planet (Maryon, 1921).

In agreement with the Reality review, Daulby truly saw himself as a prophetic artist. He viewed his music, and later his Marcotone method, as tools or catalysts for the positive evolution of mankind. However, in his essay for the Theosophical Society he specifies, “I speak as one speaking not from the past, or out of the future, but as one who desires to realize with others those things which are revealed to this present generation.” Elsewhere he remains more elusive, encouraging self-seeking: “In this short address I make no attempt to prove the full force of these statements; to attain entirely to that knowledge you must seek for yourselves this new Revelation offered in the earthly vision of Music” (1907).

Daulby’s language in his essay for the Theosophical Society is a mish-mash of esoteric perspectives. He traces a history of spiritual renewal in Western music, noting the influences of the East. Music and drama are portrayed as the key instruments of spiritual enlightenment for the current era. He praises Wagner and Chopin (“the guardians of the past”), and expresses the urgent need to establish a Christian Anglo-Saxon nationalism through music and drama.

If we are to create a National Art this religious purpose must be the foundation thereof. A temporary narrowness of vision may make this essential attribute unpopular for a day; but to make a grand tone-poem that is to be our inviolable Sagas or Vedas we must build into our art-fabric the ideal legends and sacred histories that have made us what we are in this Twentieth century of the Christian era (Maryon, 1907).

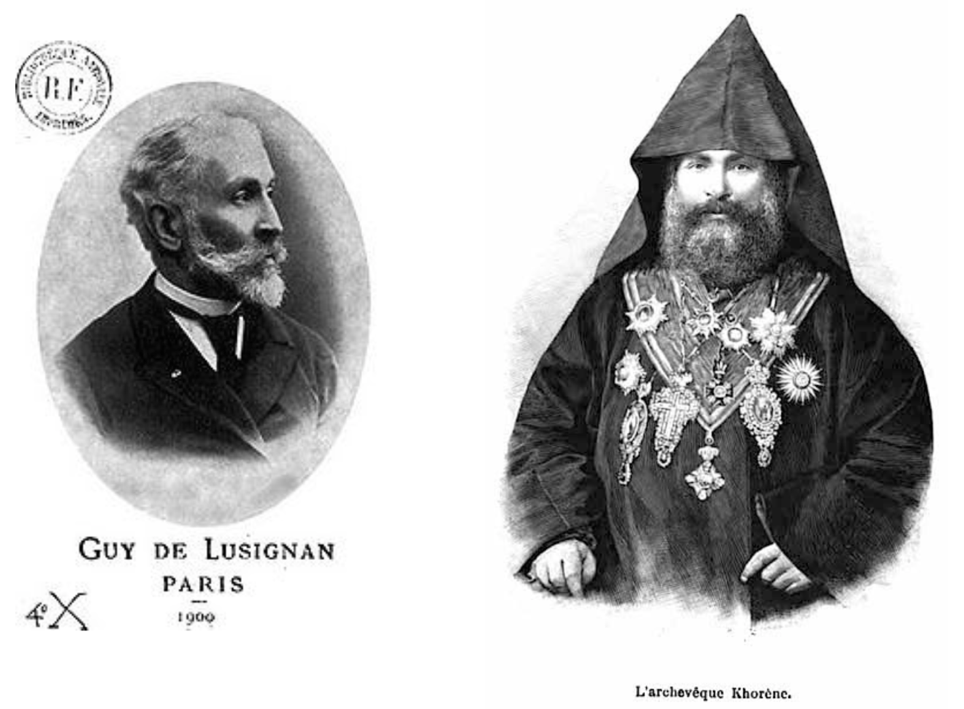

The Calfa Brothers and the Lusignan Dynasty

Right, Armenian Archbishop Corène Calfa, Guy’s brother

Over a decade before Daulby wrote his Theosophical essay, it seems he’d fallen in with a self-mythologized couple shortly after moving to Paris in 1886. In the majority of Daulby-related news references this husband and wife are referred to as “Kafta” and “Marie.” Upon deeper research I discovered their true names: Ambroise Calfa Narbey and Marie-Louise Josephine le Goupil-Calfa, who married in 1863. Calfa was an Armenian born in Constantinople and would become a Maronite priest, linguist and translator. Like Daulby, Calfa went by numerous names and titles. Incidentally, his brother Corène Calfa became Archbishop of the Armenian Church in 1875. Guy’s wife, Marie, was a French native, a wealthy humanitarian, benefactress, and landlord.

Together Calfa and Marie lived in private mansions on the Avenue d’Eylau. Also serving as landlord’s for these properties, one of their most notable tenants was writer Victor Hugo, who lived on their property for the last decade of his life. Calfa and Marie frequently attended Hugo’s salons and unsuccessfully encouraged him to join their esoteric society. The couple also made some money selling customized chivalric and dynastic orders to interested customers.

In 1878 Calfa and his brother Coréne received a letter they claimed was from a “cousin of their father,” Prince Louis Christian de Lusignan. They took this to be a “letter of recognition,” or a confirmation of their lineage within the Lusignan family tree. The Lusignans were a heraldic dynasty that flourished during the 12th-15th centuries throughout Europe and the Levant. Genetic members of the family include a long list of princes, counts, lords, and crusader kings. “The Lusignans,” notes historian Paul Sire, “accumulated an impressive array of titles that extended their influence almost as far and wide as the Roman emperors had done.” And, it would seem, the Lusignan’s found a foothold on the future through Calfa and Marie, or so the couple believed.

After reading the letter from Prince Louis de Lusignan, the Calfa brothers re-interpreted their family name, Narbey, to symbolize the connection: “Nar,” is an Armenian word for “fire”—a reference to the Latin lux (“light”), which they corresponded with the “Lus-” in Lusignan. While “Bey” referred to their rank by the Ottomans—the suffix “bey” meaning “chief” or “ruler.” Alternatively, another source stated that Calfa proclaimed Marie to be the descendant of the Lusignan family. Whether in truth or wishful thinking, from this point forward Calfa identified himself as Prince Guy de Lusignan and Marie as Princess de Lusignan of Cyprus, Jerusalem, and Armenia. But Marie would prove the most influential on Daulby through her resurrection of the ancient secret society, the Order of Mélusine.

Marie le Goupil-Calfa and the Order of Mélusine

Right, as drawn by John Sartain, date unknown.

Legend has it that the Lusignans were originally descendants of Mélusine, the child of a mortal man and a fairy mother. Mélusine remains a captivating mythical figure, in many cultures represented as a feminine water spirit with reptilian, fish, or dragon characteristics. She is often depicted taking a bath, in lakes and oceans, or near some symbol of water. And, incidentally, Mélusine is also the mermaid featured in the logo of Starbucks Coffee. This connection between Mélusine and the Lusignan dynasty was depicted and popularized by Jean d’Arras’ romantic prose work, Mélusine. Like d’Arras, Calfa, Marie, and Daulby would become caught up in dynastic mythology which they embraced through history, romance, and fantasy. Marie became fascinated. Researching the myth, she discovered the Ancient Order of Merit of Mélusine, which originated in 12th century Jerusalem. The order was instituted by Jerusalem’s King, head of the house of Lusignan d’Outre Mer.

Marie effectively revived the Order in 1881, espousing it as a chivalric order and secret society with humanitarian aims. Cardinal Ferdinand bequeathed the official ribbon of the l’Ordre Royal de Mélusine on July 25th, 1882. Marie would publish the statuts (or laws) defining the new Order in 1883. These were re-published with an additional notice historique, or genealogical history in 1885. Marie announced her full name as:

Chevalerie d’Honneur de Son Altesse [“Honorable Knight of His Highness],

Marie de Lusignan,

Princess of Cyprus, Jerusalem, and Armenia.

According to Marie’s statutes, she herself possessed the highest office, and all decisions regarding the order and its members were made through her. The Order practiced rituals of initiation and consecration with symbolic imagery, objects, uniforms, and movements. The order was rooted in a Christian humanitarianism, supporting social harmony and the arts and sciences.

[Le Chevalerie De Mélusine n’a pas été créée dans le but de satisfaire de petites ambitions personnelles, mais elle est destinée a servir de récompense et d’encouragement aux merites et aux vertus, à donner une puissante impulsion au progrés intellectuel, au développement d’une bienfaisance éclairée, et à contribuer ainsi à la solution des grans problems sociaux qui agitent l’humanité.]

The Order of Mélusine was not created with the goal of satisfying small personal ambitions, but is destined to reward and empower by its merits and virtues. [It is destined] to provide a powerful impulse in developing intellectual progress, and thus contributing to the solution of the great social problems that agitate mankind (Lusignan, 5-6; English translation by author).

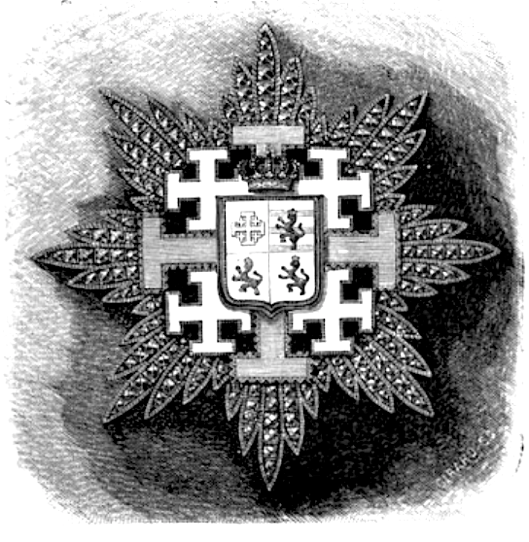

Men joined the society as an aspiring “Chevalier” (Knight), women as a “Dame d’honneur” (Maid of Honor). Based on their deeds and achievements members could be promoted to progressively more revered titles: Officer, Commander, Grand Officer, and Grand Croix (Grand Cross). While Marie held the title “Le Grand Maitrise” (the Grand Mastership). Ascension through the Order’s titles did not begin, however, until after four years of affiliation with the Order. New ranks were then bestowed to members based on the individual’s charity, good deeds, and progressive productivity in the arts or sciences.

Marie established her Order based on three preceding Orders associated with the Lusignan family. The Ordre de Mélusine was founded by the Queen, Sibylle, in 1186. The Ordre de L’Épée (Order of the Sword) was a chivalric military order founded by the King of Jerusalem (Guy de Lusignan) in 1193. Marie also cited another Lusignan tradition, the more religious Ordre de Sainte-Catherine, founded in 1063. These ancient traditions and philosophies were effectively resurrected by Marie as Grand Maitrise of the Order of Mélusine.

[Les Chevaliers de l’Ordre de Mélusine étaient agrées par la Reine, ou, à son défaut, par une princesse de la Maison royale. Ils étaient tenus de pratiquer les vertus humanitaires, de briller par leur dévouement à al foi chrétienne et de se faire les propagateurs de la Religion, de la Charité, des Arts et des Sciences.]

The Knights of the Order of Mélusine have been approved by the Queen, or, in her absence, by a Princess of the Royal House. They are bound to practice humanitarian virtues, to shine by their devotion to the Christian faith, and to make themselves the propagators of Religion, Charity, the Arts and Sciences.

An obituary for Louis de Lusignan, a biological member of that family, referred to his “tireless but unsuccessful attempts to restore his kingdom.” So, perhaps out of desperation, Louis did confer the title to Calfa or Marie before he died, or they simply conferred titles to themselves. It should be noted however that Louis’s son, Michael, legally challenged the genealogical claims of Calfa and Marie in 1903. Louis’ obituary—published the year after Marie founded the Order—paints an ominous critique of Daulby, Calfa, and Marie.

Though he [Michael Lusignan] has inherited the family name, he has not inherited the family folly, for, wiser than his father, he sees that an age in which reigning monarchs can hardly hold their own is not a favorable one for royal pretenders, either true or false (“The King of Cyprus”).

Nevertheless, Marie’s Order of Mélusine still exists today, as the Ordre Royal de Mélusine, based primarily out of Lusignan, a small town in Western France. This community of 3,000 or so is home to the ancient Chateau de Lusignan; and the inhabitants of Lusignan are called Mélusins and Mélusines. Current members still adhere to initiatory rights and the humanitarian Christian philosophy originally espoused by Marie. On the Order’s official website (www.ordredemelusine.com), the Grand Maitrise is honored as their founder. In fact, likely due to Daulby’s criminal record, the current Order claims their tradition died with Marie, only to be resurrected by the current members in 2006.

Beginning as the masseur for the Order, Daulby would rise to the ranks of Grand-Croix and “Grand Master.” In court proceedings from 1910, Daulby’s relationship with Kafta and Marie is recounted as follows.

This man it was, bearing the name of Kafta, who pretended to revive the Ancient Order of Merit of Mélusine, first instituted in 1100 by the King of Jerusalem, head of the house of Lusignan d’Outre Mer. Kafta declared that his wife was descended from Guy de Lusignan, a valorous crusader. He styled her Princess of Lusignan, of Cyprus, of Jerusalem, and of Armenia, while he himself took the rank of Prince of Lusignan. The Princess, it appears, brought him a considerable fortune. The Order of Mélusine was used by them rather to procure entrance to certain grades of Paris society than for gain. Her Serene Highness the Princess of Cyprus and Jerusalem was attracted by the personal qualities of a young Englishman named Dolbey, who performed the offices of masseur for his serene highness Prince de Lusignan, and she appointed him Secretary General of the Order of Mélusine.

After befriending the couple and serving as their masseur, Daulby would develop a more intimate relationship with Marie. It was during this embrace of Mélusine philosophy that John Edward Daulby took the royal, French, apostrophed name of “Count d’Aulby.” And following Calfa’s death in 1905, Daulby held the titles of Secretary General, Prince of Lusignan, and Grand Master of the Ancient Order of Mélusine.

“Comparatively humble up to that point,” one newspaper recounts, Daulby threw himself passionately into the Mélusine and Lusignan mythology. I can only assume that Daulby found funding for some of his operas through Prince and Princess Lusignan at this time. But his embrace of the Order appears to have been in earnest.

As an outgrowth of his Lusignan study, Daulby became enamored by the legends of King Arthur and the Holy Grail, which he referred to as the “High History of Sangraal.” Daulby’s was a form of mythic nationalism, romanticizing Anglo-Saxon and Celtic folk mythology, and believing music was the most effective and powerful means of “spreading the gospel” of a nationalist spiritual revolution. Writing for the Theosophical Journal in 1907, Daulby doesn’t hesitate to express the adoration of his mythical heritage and its instrumental role in the arts and the Universe:

The High History of Sangraal belongs not to Saxons, but to Anglo-Saxons; its environment is neither the Wartbürg nor Montsalvat; its home is our own Avalon, and great King Arthur and his glorious knights, mythical if you will, (for is not man’s Mythology among the best things about him?) are the true guardians of the shrine which contains the grandest and greatest legend in Christendom. Therefore, let us conscientiously make our true High History of Sangraal the forerunner of our National Tone-Drama, and clothe it in the Celtic mysticism that Burne-Jones, Mallory, Tennyson, and a galaxy of our English seers have woven into a splendid heritage for us. With “Sangraal” as the first stone in our art-structure [one of the seven movements in his operatic heptalogy] we may proceed. Glowing under the inspiration of native ideals, with a finer intuitional and a completer technical knowledge of our universal subject…

Daulby ended up gaining immense wealth and prestige throughout the first decade of the 20th century. But his pursuit of grand titles wasn’t purely spiritual. Earlier, while he was living in Dresden during the late 1880s, Daulby had befriended a self-proclaimed “Italian Consul” named Carducci. Carducci suggested that Daulby naturalize himself in Italy in order to purchase a noble Italian name and property—all with the aim of having his music funded and thus more regularly performed and received. However, it seems this “Italian consul” was a swindler. “Carducci had sent me papers,” Daulby recalls, “establishing my naturalization as an Italian, and proving the purchase of the Borghetto property, which was 1,800 pounds. Later, when I had returned to Europe, I learned that Carducci had sent me false papers, and further that he had been arrested and condemned” (“Count D’aulby”). Nevertheless, Daulby moved to New York in 1895, hailing himself as “Count Jean d’Aulby” and “Prince del Borghetto.” Shortly after arriving, his royal lifestyle would be further enhanced when he fell in love with a young wealthy New York socialite.

Count and Countess d’Aulby

Count D’Aulby declared that he was a connection of the Prince di Lusignan, an Italian nobleman living in Paris. Had those to whom he told this detail taken the trouble to inquire they would have found that there is no Prince di Lusignan in existence. The House of Lusignan went out of existence two centuries ago (“Her Count Was Bogus”).

In an article in the Parisian Le Figaro, Daulby claimed that he took the name “Count d’Aulby” at the age of 18, while studying at the Conservatory (Claretie). He claimed the name d’Aulby was part of a “family tradition,” via his mother’s side. When Daulby first came to America in 1892, he was introduced as Count d’Aulby.

On March 7, 1895, Daulby wedded Mrs. Francesca Lunt at Trinity Church in New York. Mrs. Lunt them became Countess d’Aulby. Marrying Mrs. Lunt, Daulby inherited approximately $146,000 (“Calls d’Aulby”). Their wedding was an extravagant affair reflecting Daulby’s role in the Order of Mélusine and the couple’s lavish lifestyle. Daulby himself had even composed “special music which was to be performed at the wedding.” And as for his wardrobe that day, “he appeared in fanciful costume, which he declared was the court dress of the princely family of Lusignan.” While the New York Times wrote of the wedding that Daulby was from Rome, Italy, that he had fought in the Italian army, and that his wedding attire was his “Lieutenant’s uniform” (“A Day’s Weddings”). Here we can see how Daulby’s biography was getting understandably confused in the media.

Fig. 12. Daulby (right) and Francesca Lunt at their Wedding in Trinity Church, NYC (“d’Aulby Protégé”)

Upon first moving to Paris Daulby worked odd jobs—cashier, man servant, commercial traveler, grocer, masseur, manicurist. The day after French President Marie François Sadi Carnot was assassinated, none other than Daulby served as the Italian interpreter, translating the replies of the anarchist assassin, Sante Geronimo Caserio. Daulby’s low-level jobs didn’t last for long. Within the first few years or the 20th century, he would become the Grand Master of the Order of Mélusine, while also bearing the name of Count d’Aulby de Gatigny. Marrying into wealth, via Mrs. Lunt or Countess d’Aulby, and selling paintings for high profit—Daulby found himself in social and financial abundance.

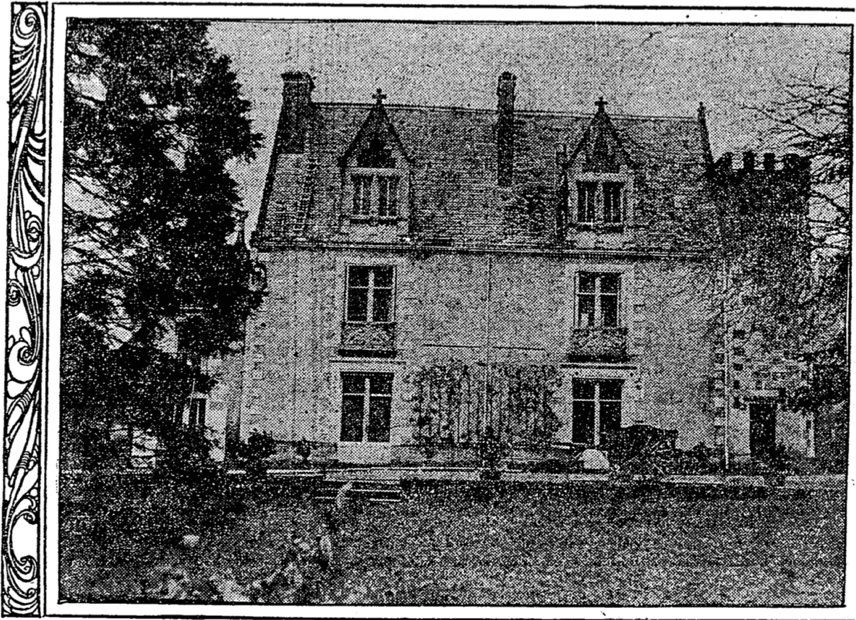

In 1902 Daulby and his wife moved to Tours, France at Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire, where he had purchased the Chateau de la Tours, the former hunting lodge of King Louis XII (“John Manning Back”). They would live in this luxurious property for 8 years, raising their four children (Guy, Frank, Isolde, and Sylvia). This was also where Daulby stored his collection of paintings—both authentic and fake. While living at the Chateau, the Count and Countess kept “numerous servants, horses, and motors, and [they were] well known in the aristocratic valley of the Loire” (“Arrested ‘Count’”). Despite having been duped by the false nobility of Carducci in Dresden, Daulby seemed increasingly drawn to using the deceptive illusion of aristocracy to support his own musical career, whose ambitious realizations were not cheap.

Daulby was notably friends with William Morton Fullerton, the London Times Paris correspondent (and lover of renowned novelist Edith Wharton). Fullerton, while already in an adulteress relationship with Mrs. Wharton, also committed adultery with Daulby’s own wife, Countess d’Aulby (Lee). Meanwhile, it seems, that Daulby had been lovers with Calfa’s wife Marie, “Princess of Lusignan.” Adultery surfaces again, and perhaps helped catalyze the release of Daulby from prison, after being accused of criminal forgery by a wealthy Duchess in 1910.

The Infamous Trial of the Count and the Duchess

D’Aulby, who, under the French system, is constantly questioned on various points brought out by witnesses, shows signs of breaking down as a result of the ordeal. As M. Diot and others lauded him today, D’Aulby sat with his head bowed on his knees, a handkerchief hiding his features. It is announced that he has spent eight months of his prison life in composing music and in writing his memoirs.

At the turn of the century Daulby was having trouble getting his “Christian era” operas performed in Paris. “Having no money to get them performed,” he reflected in court, “I conceived the idea of selling some pictures my uncle, George Danton, of London, had left me.” Daulby would continue collecting and selling paintings for the next two decades. Sometime in the first decade of the 20th century, he settled down in Lyons to focus on art collecting and selling. Unfortunately, Daulby’s role as an art dealer turned out not to be entirely ethical. The shadier side of Daulby’s art dealings seemed to have begun when he began working with William Lofty Van Rutan, a seller of “old master” paintings in London’s Soho district. Van Rutan and Daulby became close—Van Rutan would be the best man at Daulby’s wedding. The media would unsympathetically portray their story as court information trickled into the newspapers:

Van Rutan, like Dolbey, was extravagant and greatly desirous of obtaining money. Just when the plot was hatched which resulted in the journey to America is, of course, known only to these two worthies. It is possible that its late developments were undreamed of by either of them.

Their primary intention in coming to America was to sell a number of paintings of the “commercial old master” order which Van Rutan had picked up in London. It must have occurred to one of them that it would be a magnificent advertisement for the pictures if they were represented as being the collection of some noble house. Dolbey and Van Rutan got together all the money they could, bought gorgeous frames for the pictures and took saloon passage for New York.

It wasn’t until 1910 that a loyal customer caught on to Daulby and Van Rutan’s swindle. This client was the Duchess de Choiseul-Praslin, aka Mrs. Lucy Tate Hamilton Paine, former wife of Charles Hamilton Paine (a.k.a. “The Copper King of Boston”). After her husband died she married the Duke de Choiseul, son of the wealthy Forbes family. Following Mr. Paine’s death, the former Mrs. Paine decided to insure their collection of paintings. In reviewing the paintings of Daulby, art expert Roger Miles determined them to be “unmistakable forgeries.” Daulby and his wife were then accused by Mrs. Paine of selling her $200,000 worth of fake versions of masterwork paintings. A lengthy, dramatic, and heavily reported court battle ensued.

During his initial court trial, Daulby denied that he presented the paintings as “genuine.” His primary defense was that he was unaware of the falsity of his wares and that the authenticity of his paintings had been confirmed by “American experts,” such as Henry G. Marquand, President of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (“Calls D’Aulby’s”). In fact, in 1891 Daulby had loaned several paintings that were exhibited at the Met (Trumble).

The court proceedings would often get rowdy and boisterous. After Daulby accused those who disbelieved his claims as “liars,” Judge Roberts demanded, “What do you call yourself?” To which Daulby insisted “An honest man!” (“Calls D’Aulby’s”). There were accusations, attacks, riots, cries, and cheers throughout the Daulby/Choiseul-Praslin case, which became international news for the entire year of 1910. In an earnest plea for sympathy, according to one news article, Daulby was said to have proclaimed:

The object of his life was to build up a reputation as a musical composer. He maintained he had sold pictures, furniture, and wine to Mrs. Paine at her insistence, and had never guaranteed the authenticity of the pictures […] She invaded his house, he said, and eventually their relations became very friendly. They were broken, however, for personal reasons (“Count Defends”).

The court case then only became more complicated with the inclusion of affairs and blackmail. Personal letters of the Duchess, leaked by a Russian peasant, Alexandre Tscherniadieff, who was also posing as a count, implicated that she and Daulby had been lovers. Tscherniadieff was accused of blackmailing the Duchess and was ultimately arrested. However, once the letters came to light in court, they revealed the Duchess’ strong feelings for Daulby—“her affection,” she wrote in one letter, was “an incandescent flame” (“Love Letters Read”). This then made her case against Daulby appear as a lover’s vengeance. Countess Daulby said in court of this affair, “I did not know her relations with my husband until later, but if I had known I would have driven her out like the shameless viper she was” (“Calls D’Aulby’s”). Ultimately the Duchess dropped her suit against Daulby. In fact, she never appeared in court again following the opening case (“Count d’Aulby at Liberty”). When this was announced in court, there were reportedly loud cheers and cries of “Long live d’Aulby!”

Meanwhile, an imprisoned Daulby had been falling apart. Due to the court case he had to forfeit his Italian property and title, “Prince de Borghetto.” He began selling off his Mélusine regalia and decorations for profit, while Marie, the “Princess of Lusignan,” could not be found (“Daulby Protégé”). Daulby was struggling psychologically, finding catharsis and hope only through music.

Nevertheless, the French court continued to pursue the case against both Daulby and Lunt. Daulby was defended by French citizens who sited numerous charities that the Count had organized in France. And in general, the French court pitied or was charmed by Daulby. When the Duchess left Tours on Christmas of 1910, the town was “filled with rumors that the inhabitants were planning a demonstration hostile to her” (“Duchess Flees”). On January 2, 1911, Francesca Lunt was freed, as the Duchess’ prosecutor abandoned the case. A few days later, on January 14, Daulby was found guilty of swindling Mrs. Paine a fake painting by Corot bought for $80 and sold for $1,200. He was sentenced one month in prison. However, as he had already spent 9 months in prison, Daulby was immediately released.

Following the court proceedings, Mrs. Lunt’s mother committed suicide, by drowning herself in a well, at their family cottage in Scituate, Massachusetts. Mrs. Lunt’s brother also committed suicide around the same time. “It was believed,” one journalist wrote of the mother’s death, “that the troubles of her daughter had unsettled her mind.” Daulby was said to have retreated to the same Scituate cottage after his release from prison.

It was largely through the media coverage of this trial that Daulby’s diverse identities rose to the surface. Though they began to be connected, there never was an exhaustive portrayal of this Dickensian chameleon. Whether he had been deceiving himself or others over the years, Daulby could no longer claim royalty or high title following the trial. He was forced to rethink his life and redefine himself, yet again.

During the trial he alluded to the importance of music in his life. All through his imprisonment he had been thinking about music and the relationship between tone, color, and Divine cosmology. Moving to New Jersey, Daulby did not retire in reclusion. Rather he returned to his composer identity, Edward Maryon. Under this renewed persona, with much less aristocratic airs, he worked steadfastly to design, teach, and promote his life’s most ambitious work: Marcotone.

Marcotone: The Science of Tone-Color

The international acceptance of “Marcotone” will make the whole world akin musically, and what more powerful factor toward peace and progress can be looked for than a world governed by arbitrary laws, enforced frontiers, foreign tongues, becoming united by the divine art and universal language of music (1921).

Edward Maryon

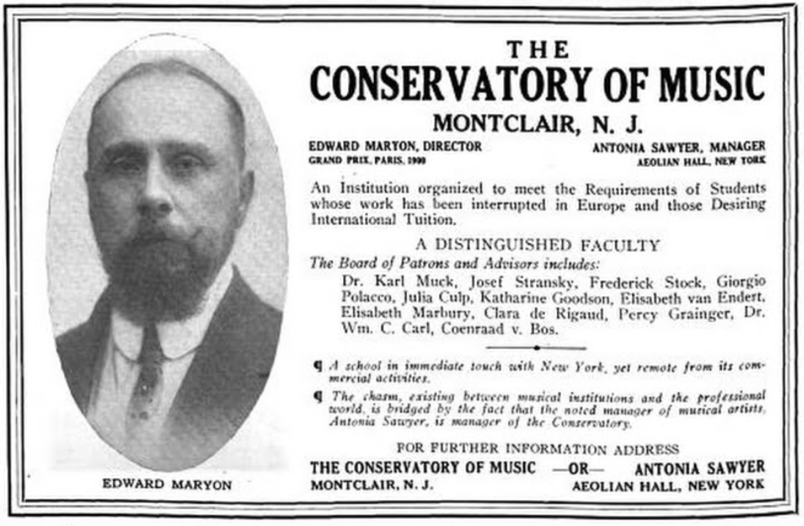

Daulby moved back to New York in 1914. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Montclair, New Jersey, where he would co-found and serve as director for the Montclair Conservatory of Music. In this role he also initiated an exchange fund for British and American music students. In a lecture inaugurating the opening of the Conservatory in 1915, Daulby dismissed commercial affairs in a musician’s life while emphasizing a more divine agenda. “Not alone should the student become a specialist on a given instrument, or a mere vocalist, but a thoroughly trained musician, cultured in the sciences, literature, history and ethics of the divine art” (“Maryon Outlines”).

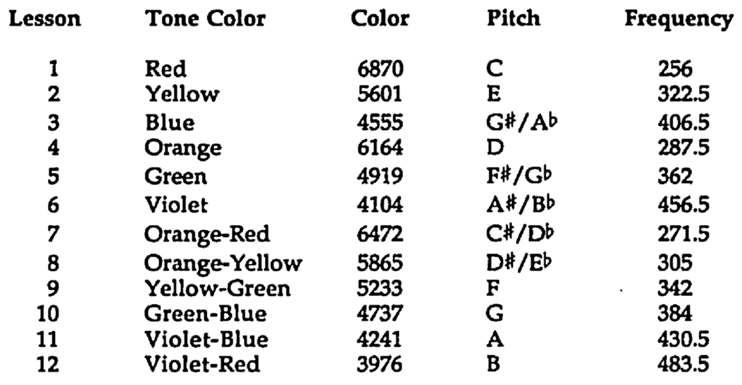

Following his release from prison, Daulby’s main concern was in refining and promoting his emerging tone-color science, which he called “Marcotone.” The word “Marcotone” is an esoteric acronym (“Ma-R-Co-Tone”): “Ma” is derived from the Hindu term meaning “to measure”; “R” stands for the first letter in raga, the Hindu term for melodic interval or “scaling”; “Co” is the initial syllable of the word “color”; and “tone” refers to musical pitch.

Inspired by the related tone-color science of Crookes, Flammarion, and other scientifically inclined esotericists of the time, Daulby set about finding the unity of tone-color by the theoretical correspondence of their rates of vibration. Quoting French Naturalist, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck—“the function creates the organ”—Daulby believed that he could create a new audio-visual mental faculty with his Marcotone method. From the beginning Daulby aimed to develop a new audio-visual sensibility, one that would become automatic, Universal, and spiritually transformative.

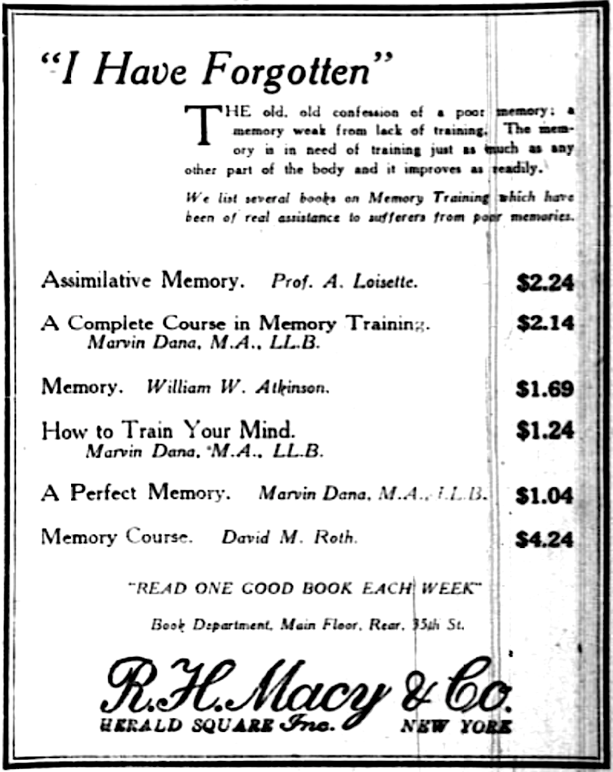

In essence, Daulby had designed an “art of memory” of his own. He took the basic premise of Dana’s practical mnemonic work and steeped it in an esoteric perspective revering the symbolic relationship between tone, color, and number. More like the ars memoria of Giordano Bruno (1548—1600), Daulby used symbolic correspondences and geometry to reach beyond human logic, towards Divine infinitude. By working within the mind, by constructing and exploring this “new” memory with the Marcotone color scale, Daulby believed we could positively evolve our individual consciousness as well as the entire human race. Marcotone was meant to be understood alongside other esoteric expressions of tone and color, which one meets in tantric traditions of Buddhism, the Kabbalah of Judaism, and elsewhere. One’s ability to memorize the Marcotone scale was of utmost importance, as it is for those esoteric practitioners of Buddhist mantra or Kabbalistic permutations of the Divine Name.

Daulby’s friend Marvin Dana, who was notably of the Chevallier grade within the Order of Mélusine, influenced Daulby’s mnemonic aspirations. Dana was a published author of grammar, math, and memory, as well of literary fiction and theatre. In the latter case he was quite successful, collaborating with Bayard Veiller and reaping praise from the likes of President Theodore Roosevelt. He focused on mnemonics throughout the 1910-20s. His A Perfect Memory: How to Have and Keep It (1917) offered an introduction to the practical art of memory using visualization, lists, and symbolic correspondences to memorize names, faces, dates, and other forms of knowledge. “Mental vision,” Dana writes, “will repay a thousand-fold every care lavished to its encouragement.” Daulby’s language in teaching and promoting Marcotone echoed the language of mnemonist and fiction writer Marvin Dana. It also appears that Daulby’s opera Chrysalis, mentioned earlier, was based on “The Moth and the Star” (1902), a short story of Dana’s.

Another important figure in Daulby’s later life was the opera singer and impresaria Antonia Sawyer (1856-1941). Sawyer would play a role in Daulby’s efforts as a teacher as well as a tone-color scientist. It also showed Daulby continuing to associate himself with New York’s “high society.” Sawyer worked with notable performers and composers—such as pianist Artur Schnabel and composer Percey Grainger. Shortly after gaining great success as a singer, she suddenly left her performance career to become, as Daulby noted, an “impresaria.” Working from an office in the Metropolitan Opera she organized and curated music events and became one of the first female managers of notable opera singers. She also became the manager for Australian composer Percy Grainger. It is likely she met Daulby when they both helped develop the Montclair Conservatory of Music—Sawyer served as the first manager of the conservatory.

Sawyer praises Daulby in her memoire, Songs at Twilight: “Of course Maryon was an ideal musician […] We were closely connected in music and in a long happy friendship.” And under the name of Edward Maryon, Daulby contributes a short essay of praise, entitled “An Artist Impresaria,” at the end of her book.

During the Summer of 1918, Daulby spent two weeks at Sawyer’s property, Camp Illahee on Great Moose Lake in Hartford, Maine. It was here that Daulby defined the precise colors to be used in Marcotone. Also with them was Ashley Miner, a respected businessman of silk and a “color consultant”—Sawyer and Miner would later marry. Sawyer recollects on the trio’s summer vacation in her memoire:

Maryon knew that Miner could be very valuable in choosing the right shades, as Miner was in the silk business and was often called upon by other silk men to decide upon different colors. Color was what Maryon desired. It would be impossible to inform my readers how much I loved the two weeks that those dear friends spent with me. They would look over Miner’s exquisite samples, when they were not walking around the great out of doors and often finding a beautiful color in my lovely flower garden (Sawyer).

After decades of intensive research, Daulby published his treatise, Marcotone: The Science of Tone Color, in 1919. Through her friendship, mutual love of music, and admiration for Daulby, Sawyer would become the manager of Marcotone, Inc. Following the publication of Marcotone, Sawyer recalls, “we were all singing by color. I was very happy over the result; the books are beautiful. It was my privilege,” she proclaims, “to be the manager for Marcotone, Inc.”

At the time of publishing the book, Daulby claims to have been developing his tone-color science for 28 years (Marcotone, 6)—so, he began working on the project some time around 1891, while living in Paris. Daulby’s conception of this practice emphasized the ability to memorize music. This could be done in silence purely by color associations within one’s mind. Daulby saw vast applications for his work. He was also considering applying it to children’s books and games, to plays and pageants.

Nature in our present stage of evolution has expressed but one scale, the spectrum, and unless our scales of color, chemistry, sound, etc., are attuned to this one revealed aspect of those cosmic negations, to those universal principles, Darkness-Silence, then their planetary manifestations as Sound and Light, will remain forever an illusion of the intellect and a delusion of the senses (Maryon, 1921).

Blavatsky’s Theosophical interpretation of sound likely inspired Daulby’s conceptual model. His tone-color correspondences were based in the understanding that the sound spectrum originates from silence, and the color spectrum from whiteness. Or, as one Theosophical student put it:

Sound is only audible to the ear – the gross sense or one of the finer ones of the same kind – when it is making some matter vibrate; just like light – which is darkness when there is nothing for it to illuminate. So the OM sounds in silence at first; it is living spiritual silence (Tingley).

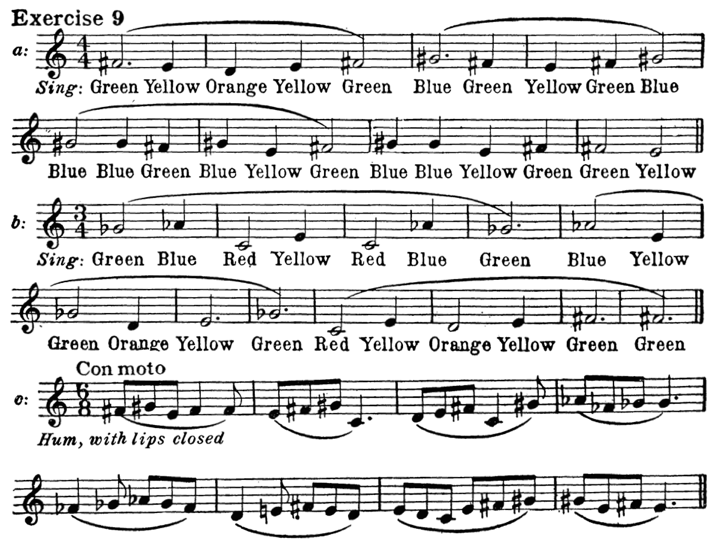

In an effort to be as faithful as possible to his frequency data, Daulby desired just intonation, but he ultimately defaulted to modern tempered notation, which he claimed had “’cribbed, cabined, and confined’ music for centuries, and should be ignored” (1919). Marcotone begins with Daulby defining basic musical concepts and notational terms. Then he begins leading the reader, successively, through each of the 12 tone-color correspondences. For each tone-color presented, he provides a notated tone-color exercise. As one progresses through the tone-colors, the exercises increase in complexity, with various tone-colors being employed. So Marcotone begins by using the voice to audibly associate specific pitches with specific colors in the mind. Daulby hoped that by the end, his readers would be able to experience these songs, soundlessly, as internally projected color-thoughts.

The application of these natural laws, through acquiring the habit, which is “second nature,” of associating a given color with a given tone, in a comparatively short space of time, gives us an automatic control of all melody and harmony, so that music can be read and memorized without any recourse to a musical instrument, in the woods and fields, on the train, or in our favorite arm chair (1919).

It seems Daulby’s Cycle of Life was composed according to Marcotone principles. His compositional reverence for the whole-tone scale was also a core aspect of his tone-color science. His tone-color correspondences were geometrically arrayed producing two whole-tone scales completing “the natural” chromatic scale. Daulby claimed that “this Chromatic Scale is a direct manifestation of the Principle of Life, universally exposed in all spheres of Phenomena.” Through Marcotone, Daulby was seeking to create a new mental faculty, that of the “Chromatic Tone-Color Scale” (1919). He also treated Marcotone as a kind of relaxation therapy, emphasizing its meditative nature. “A few minutes of quiet contemplation on matters musical, will put you in a that relaxed condition of physical and mental calmness, so necessary to the successful accomplishment of work in Marcotone.”

Marcotone was first presented to the public in 1916 in an article by A. Walter Kramer in Musical America. At the time of Marcotone’s publication Daulby claims there were 50 musicians “training in Marcotone” practice. Marcotone offered a practice and philosophy that “everybody, old and young, who realize the uplifting powers of song, dance and instrumental music” could master. Through an inspired engagement with Marcotone one could then “read, write, hear and memorize Music as they do their own language” (1919).

In the preface to Daulby’s treatise, French musicologist Raymond Duval described the songs of Daulby’s Marcotone experiments as “songs of exile, as they were written, quite untouched, in a place of solitude, so complete, that no sonorous instrument of any sort whatever, was admitted. They are remarkable examples of an interior audition—metaphysic, one may say. We have preserved them in all the power of their transcendent chromaticism” (1919). I can only assume the “solitude” and “exile” that gave birth to Daulby’s inner audition refer to the artist’s year in prison, where he likely devised innumerable songs of quiet color.

In 1891, the year Daulby claimed to have begun his research, his tone-color theory was affirmed by scientists I.J. Belmont and Charles Henry Wilkinson. Wilkinson agreed with Daulby’s tone-color relationships, the correspondence of the divisibility of the octave, and the chromatic hues that account for its twenty-four divisible sections. While Dr. Donald Andrews, at Florida Atlantic University, developed a keyboard to execute Daulby’s tone-color correspondences (Vincelli).

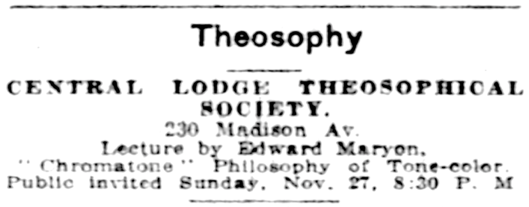

From the time he was released from prison, well into the 1920s, Daulby was regularly traveling and lecturing on Marcotone. He lectured at Colleges and Universities, Theosophical Societies, private salons, and numerous public forums. One publication I found of Daulby’s from this period was published in 1928 by the Rosicrucian journal, The Mystic Triangle. Here he restates his Marcotone philosophy, concisely yet cryptically speaking to the conceptual trinity of Number, Tone, and Color.

Number and its symbolism make possible all forms and spaces in the Universe. Tone or sound is the origin, “the creator, preserver, and destroyer of all forms” (Maryon, 1924). Color or Light is said to be “paternally fostered by sound.” From a Vedantic perspective, Daulby’s conception of tone alludes to the three principle deities of Hindu thought: Brahma (the creator), Shiva (the destroyer), and Vishnu (the preserver.) And in like manner Daulby presents sound as the primordial and pervasive source of the life of the Universe. Perhaps Daulby was even thinking of the Anahada nada (“unstruck sound”), when he pursued this silent color music of the mind? Silence also has a key conceptual role in Daulby’s philosophy. “Silence decomposed through number is sound,” Daulby writes. While the visual map of his “tone-color scale” [see, fig. __] portrays “sound/silence” and “whiteness/light” as the source of tone-color relationships. And behind this circle of concepts is a triangle recalling us to number and geometry.

Daulby sought the unification of phenomena through the variation of natural laws. The first principle of Marcotone is “vibration is the Universal Law.” What’s more he was driven by a grander view of Marcotone as a catalyst of human evolution. Through Marcotone, he writes, “Once this new and vital factor in evolution is realized by those responsible for the nation’s education, we shall become a race of natural musicians. Song will become a common, everyday gift, even as speech is today; a new joy will have come into the hearts and minds of our people, and a new and more harmonious epoch of life will fill the earth” (1919). Marcotone offered the means by which to “attune the little universe of [one’s] own Mind in harmony with the Universal Mind of God, as He translates it in nature.”

In 1943, however, Daulby’s tone-color science came under attack by renowned music journalist, Percy Scholes (1877-1958). In his writing for the Oxford Companion to Music Scholes publicly accused Daulby’s science of being “without scientific foundation” (Peacock). Still today, Daulby’s Marcotone cannot be said to be based in traditional science. Rather his is an imaginative poetry of tone, color, and spiritual philosophy, which, at the very least, offers a unique method of multi-media meditation and artistic experimentation. Though his Marcotone theory was generally rejected by the science community and the larger musical world, it would find an enduring home in the traditions of Western esotericism.

Paul Foster Case (1884—1954) was an American occultist and a prolific author on occult subjects. He was also the founder of the Builders of Adytum (BOTA). BOTA was formed in 1922 in Los Angeles as a secret society inspired by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the Masonic tradition. Further inspired by Daulby’s work, Case adapted the Marcotone system as a fundamental aspect of his esoteric philosophy. He applied Daulby’s tone-color pairs to the Kabbalist cube of space, making other correspondences with Hebrew letters, gematria (numerology), cardinal directions, astrological signs, tarot cards, and the alchemical elements. BOTA is still active today.

In 1933 Daulby had decided to return to his native country, first moving to London where he would live for over a decade. “It has been quite a loss to all us,” Antonia Sawyer recalled in 1939, “since Edward Maryon decided to spend so much time in Europe” (Sawyer). In 1942 he settled in Cheltenham, England. Still carrying an archive of old paintings, he was granted the opportunity to store his paintings in the basement of a local gallery. The gallery occasionally exhibited authentic paintings from Daulby’s collection, such as Murillo’s “The Flower Girl” (Maryon, 1942).

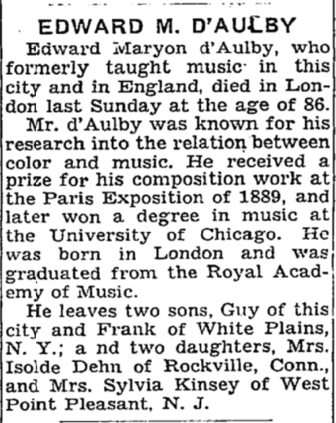

Little else is known of Daulby’s final decades in his native England. As mentioned earlier, many had presumed him dead. Mrs. Francesca Lunt died on January 12th, 1947. Seven years later, at the age of 86, Daulby died in London on Jan 31, 1954, survived by his four children: daughters Isolde Dehn and Sylvia Kinsey and sons Guy and Frank Daulby. Following his death, Daulby’s archives were donated to the Boston Public Library [n.b. the BPL has been closed for renovations and inaccessible as I’ve worked on this essay and until 2019].

Perhaps in large part due to his variable aliases, the New York Times obituary for Daulby did not even mention his role as an art dealer, nor his court case (which The Times covered thoroughly throughout 1910), nor his royal titles and elite social circles. Daulby died, “Edward Maryon d’Aulby”—a composer and educator, the author of Marcotone, and a father of four. I imagine, that’s how he would have liked to have been remembered. While Antonia Sawyer wrote in her memoire, “It would take an extra book, or part of one, to describe the works of this talented musician.” Daulby’s musical works are lacking to us now, while his later Marcotone compositions were intended to be inaudible. Perhaps Miss Sawyer would likely be surprised what such a book might nevertheless tell. Did she know the whole story? Did anyone?

Daulby’s materialistic and criminal forays paint him either as a vein manipulator or a victim of his own naïveté. I lean towards the latter. It seems Daulby found himself in numerous compromising situations due to his gullibility and naïveté, if not also his philandering—I’m thinking of Carducci’s fake property, Marie and the legitimacy of the Lusignan line, the Duchess’ letters. In all my research I sensed a strong earnestness and conviction when it came to Daulby’s spiritual and artistic path. And while Marcotone may never lead to the spiritual evolution of the human race, the “inner audition” and intuitive discipline that Daulby devised and championed deserves a unique place in the history of esotericism in Western music. While his colorful life is surely the stuff of novels and movies.

©2017 Matt Marble

Matt Marble is a composer, musician, writer, and visual artist. He holds a B.A. in Speech & Hearing Sciences from Portland State University and a Ph.D. in Music Composition from Princeton University, where he wrote his dissertation on the role of Buddhism in the music of Arthur Russell.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOOKS

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. Studies in Occultism: The Esoteric Character of the Gospels. The Aryan Theosophical Press. Point Loma: 1910.

Brent, Joseph. Charles Sanders Peirce: A Life. Indiana University Press. Bloomington: 1998.

Crary, Jonathan. Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture. MIT Press. Cambridge: 2001.

Dana, Marvin. A Perfect Memory: How to Have and Keep It. Edward J. Clode. New York: 1917.

Dann, Kevin T. Bright Colors Falsely Seen: Synaesthesia and the Search for Transcendental Knowledge. Yale University Press. New Haven: 1998.

De Lusignan, Marie (trans. Matt Marble). Ordre de Mélusine. Typographie Morris Pére et Fils. Paris: 1883.

Hipschcr, Edward Ellsworth. American Opera and Its Composers. Theodore Presser Co. Philadelphia: 1927.

Horton, Frank H. “Tone and Color Harmonies.” The Illustrated American. Volume VIII. The Illustrated American Publishing Co. New York: 1891.

Johnson, Harold Earle. Operas on American Subjects. Coleman-Ross Co. New York: 1964.

Lee, Hermione. Edith Wharton. Vintage Books. New York: 2008.

Luce, Henry Robinson. Time. Volume 73. Time Inc. Chicago: 1954.

Maryon, Edward. Marcotone: The Science of Tone-Color [a]. Marcotone Company, Inc. New York: 1919.

Marcotone: The Science of Tone-Color [b]. C.C. Birchard & Company. Boston: 1924.

Musical News. Volume XXXIV. Nos. 879 to 904. January to June. London: 1908.

Rush, Mark Alan. An experimental investigation of the effectiveness of training on absolute pitch in adult musicians [Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University]. University Microfilms International. Ann Arbor: 1989.

Sawyer, Antonia. Songs in Twilight. The Devin-Adair Company. New York: 1939.

Seekins, Brenda. Around Great Moose Lake. Arcade Publishing. Charleston: 2006.

Sire, Paul. King Arthur’s European Realm: New Evidence from Monmouth’s Primary Sources. McFarland & Company, Inc. Jefferson: 2014.

Tingley, Katherine Augusta Westcott. The Theosophical Path. Volume 16. January—July, 1919. New Century Corporation. Point Loma, 1919. Pgs. 172-173.

Trumble, Alfred. The Collector. Vol III., No 1. Nov 1, 1891.

Vincelli, Joseph. The Art of Tone: Understanding Our Love for Music. Ginosa Publishing. Dallas: 2003.

Wagner, Richard. Richard Wagner’s Prose Works. Volume VI: Religion and Art. Kegan Paul, Trübner & Co., Ltd. London: 1897.

Weldman, Jeffrey. Artists in Ohio, 1787-1900: A Biographical Dictionary. Kent State University Press. Kent: 2000.

PERIODICALS AND OTHER DOCUMENTS

“Arrested ‘Count’ Son of a Braintree Tailor,” Essex County Chronicle. Frid, April 29, 2010. Pg. 2.

“Calls d’Aulby’s Accuser a ‘Viper,’” New York Times. Thursday, Dec. 22, 1910. Pg. 4.

Case, Paul Foster. “The Correlation of Sound and Color.” Hestia Publishing Co. Boston: 1931.

Claretie, Georges. “Gazette des Tribunaux,” Le Figaro. Mercredi 21, Décembre, 1910. Pg. 4.

“The Conservatory of Music” [Advertisement], Musical America. July 13, 1915. Pg. 8

“Count D’aulby at Liberty: Practically Wins Case Brought by Duchess de Choiseul in France,” Chicago Tribune. Sunday, January 15, 1911. Pg. 2.

“Count D’aulby: Extraordinary Career of Essex Man,” The Daily News. Saturday, April 23, 1910.

“Count D’aulby at Liberty: Practically Wins Case Brought by Duchess de Choiseul in France,” Chicago Tribune. Sunday, January 15, 1911. Pg. 2.

“Count D’aulby’s Chateau de la Tour and the ‘Count’ and his American Wife at Their Trial in France,” New York Times. Sunday, January 1, 1911. Pg. 3.

“’Count’ Defends Swindling Charge,” San Francisco Call. Wednesday, December 21, 1910. Pg. 9.

Crump, Basil. “Richard Wagner’s Music Dramas,” Theosophy. Vol. 11, No. 1. 1896. Pgs. 23-25.

D’aulby, Edward M [Obituary]. New York Times. September 14, 1884. Pg. 19.

“D’aulby Protégé of Pseudo Prince,” New York Times. April 24, 1910. Pg. 24.

“A Day’s Weddings: D’Aulby-Lunt,” New York Times. March 8, 1895. Pg. 8.

“Duchess Flees; Drops Suit,” Chicago Tribune. Sunday, December 25, 1910. Pg. 2.

“Duchess Weds a Duke,” Oakland Tribune. January 7, 1911. Pg. 12.

“Her Count Was Bogus,” Hornellsville Weekly Tribune. Friday, February 19, 1897. Pg. 2.

“I Have Forgotten” [advertisement], New York Times. Saturday, March 19, 1921. Pg. 3.

“John Manning Back From Europe,” Musical Courier: A Weekly Journal Devoted to Music and Music Trades. Volume 57. Musical Courier Company. London: 1908. Pg. 33.

“The King of Cyprus,” New York Times. September 14, 1884. Pg. 12.

Kramer, Walter. “To Teach Absolute Pitch By Color Sense,” Musical America. November 4, 1916. Pg. 19

“Love Letters Read at d’Aulby’s Trial,” New York Times. Friday, Dec. 23, 1910. Pg. 4

Maryon, Edward. “The Theosophical Society and Music,” Transactions of the Second Annual Congress of the Federation of European Sections of the Theosophical Society Held in London July 6-10, 1905, Pg. 365-373. Theosophical Society, London: 1907.

“When Busoni Excelled Himself,” Musical America. Sept. 14, 1915. Pg. 28

“Marcotone.” Reality [Baha’i publication]. March, 1921. Pgs. 23-25.

“Color Vibrations and Music.” The Mystic Triangle [San Jose AMORC publication]. Vol. VI, No. 4. May, 1928. Pgs. 438—440.

“Maryon Outlines Conservatory Plans,” Musical America. July 3, 1915. Pg. 16.

Musical Times. January to December 1954. Volume XCV. Pg. 152.

“The ‘OM’—A Study in the Upanishads,” The Theosophical Path. Vol. XVI, No. 2. February, 1919.

“Pseudo Count Tried at Tours for Swindling,” The Oregon Daily Journal. Thursday, Jan. 19, 1911. Pg. 13.

“Theosophy” [Advertisement], New York Times. Saturday, November 26, 1921.

FIGURES

Fig. 1 & 2. Left, a photo of Daulby (signed “Edward Maryon”) from his book Marcotone.

Right, the tone-color correspondences of Marcotone theory

Fig. 3. Daulby as a schoolboy in Essex, England (“Arrested ‘Count’”)

Fig. 4. Concert listing of Daulby’s “Beatitudes” in Musical Times, January 1, 1908

Fig. 5. Esoteric philosopher and writer, Edouard Schuré

Fig. 6 & 7. Left, Guy de Lusignan (Ambroise Calfa);

Right, Armenian Archbishop Corène Calfa, Guy’s brother

Fig. 8 & 9. Marie de Lusignan. Left, portrait from 1882; Right, as drawn by John Sartain, date unknown.

Fig. 10. Marie le Goupil’s published statutes of the Order of Mélusine (1883)

Fig. 11. Plaque of the Grand-Croix (“Great Cross”) and the Grand-Officier (“Grand Officer”)

Fig. 12. Daulby (right) and Francesca Lunt at their Wedding in Trinity Church, NYC (“d’Aulby Protégé”)

Fig. 13. The Chateau de la Tours (“Count D’Aulby’s Chateau”)

Fig. 14. Count and Countess Daulby at court in Tours (“Pseudo Count Tried”)

Fig. 15 & 16. Left, Countess and Count d’Aulby pictured above the Chateau de la Tours (“Fake Count and Countess”); Right, Duchess de Choiseul-Praslin (“Widow Weds a Duke”)

Fig. 17. Chicago Tribune, January 15, 1911 (“Count D’aulby at Liberty”)

Fig. 18. Advertisement in the Musical Times (“The Conservatory of Music”)

Fig. 19. An advertisement of Marvin Dana’s memory training from the New York Times (“I Have Forgotten”)

Fig. 20. Antonia Sawyer, date unknown (Seekins)

Fig. 21. The Marcotone tone-color scale (1919)

Fig. 22. Marcotone tone-color scale–color values in Angstroms, pitch values in Hertz (Rush)

Fig. 23. Exercise 9, from Lesson V in Marcotone (1919)

Fig. 24. “Geometric color figure” from Marcotone (Maryon, 1919). The double triangle represents proportions of primary tone-colors; the dotted lines represent complementary tone-colors.

Fig. 25. New York Times ad for a Daulby lecture at the Theosophical Society (“Theosophy”)

Fig. 26 & 27. Left, Percy Scholes; Right, Paul Foster Case, drawing by Jane Adams

Fig. 28. The Paul Foster Case matrix, including Daulby’s tone-color correspondences

Fig. 29. Daulby’s obituary from the New York Times