The 19th century was definitely a curious era—an era where science, technology, and spirituality heavily intersected: Samuel Morse invented the telegraph, Louis-Jaques-Mandé Daguerre invented an illusionistic photographic process we now know as the Daguerreotype, the Fox Sisters conjured up the spiritual telegraph line, scientists were experimenting with magnetism on somnambulists as a way to “prove” existence of the souls of the deceased, infamous spirit photographers Mumler and Hudson, and Eadweard Muybridge’s first moving pictures.

Similar curiosities enchanted 20th century artists. Salvador Dalí believed the camera was a mechanism unable to censor, while Roland Barthes famously discussed a photographic practice in Camera Lucida that “would cut through the generalized image repertoire…to touch the absent real.” Barthes described the moment punctum—the point or “accident” he claimed that stood out the most. All of these processes involved ways of manipulating and distorting reality, but also existed as what seems to have been a reputable source in providing ‘evidence’ that the invisible could become visible or audible. I talked with Spiritualism photographer Shannon Taggart via email to discuss her background, process, and the psychical and chance abilities of the camera.

During this era of possibility, Spiritualism and photography were brought together in an attempt to create scientific proof of the spiritual dimension. This interplay ultimately revealed both photography’s and Spiritualism’s complicated relationship with truth.

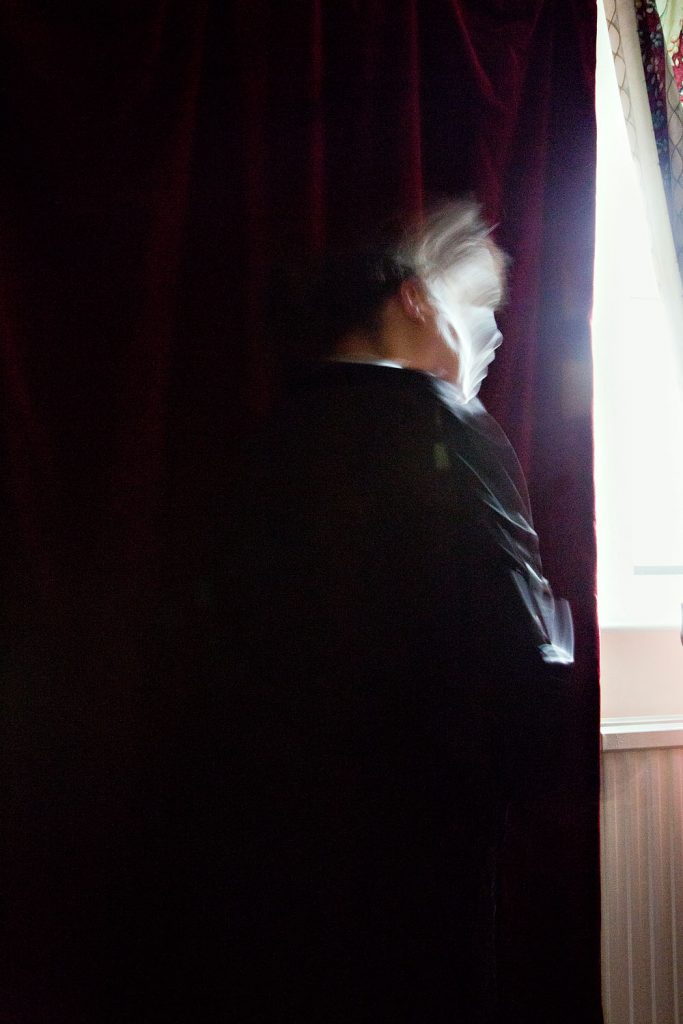

Photography’s ability to trick was made clear through its dialogue with Spiritualism. Initially thought of as an objective tool, the photographic method turned out to be full of subjective complications. Temperature variations, light leaks, motion blur, lens distortion, double exposures and other types of mechanical or chemical artifice could – accidentally or purposefully – prevent the camera from operating reliably.

Spirit photography, like other photographic representations introduced in the same era – microphotography, astrophotography, high-speed motion studies, electrographs, and X-rays – confused the relationship between seeing and knowing. – Shannon Taggart

—

E.L. Can you talk about your personal background and when and where your fascination with American Spiritualism began?

S.T. I first became aware of Spiritualism as a teenager, after my cousin received a reading from a medium who revealed a secret about my grandfather’s death that proved to be true. Since then, I have been deeply curious about how a total stranger could have learned one of my family’s secrets.

In 2001, I began photographing at the place where my grandfather’s message was received: Lily Dale, New York, the town home to the world’s largest Spiritualist community. I quickly immersed myself in the philosophy of Spiritualism—I received readings, experienced healings, joined in séances, attended a psychic college and sat in a medium’s cabinet, all with my camera. I expected to spend one summer figuring out the tricks of the Spiritualist trade. Instead, I stumbled into a hidden world with a complex history that became a resource and an inspiration for my own photographic practice.

E.L. I am curious about your take on technology’s influence on Spiritualism, as you have photographed instrumental trans-communication devices and your use of the camera alone suggests an interest in technology’s ability to reveal alternate realities or alternative ways of seeing and believing.

S.T. Spiritualists have always employed technology (however rudimentary) to amplify their connections. Trumpets, tables, talking boards, slates, canvases, cabinets, radios, cameras, video and audio recorders are used and misused in order to extend the senses and assist an engagement with the spirit world.

It is interesting to compare their use of technology (known as instrumental trans-communication or ‘ITC’) to the shamanic use of power plants – as a tool to invoke, amplify or uncover a hallucinatory experience.

E.L. Mumler, Hudson, and the Fox Sisters were eventually exposed in the late 1800s for their fraudulent and deceptive techniques: trick cameras, double exposures, costumes, a string tied to an apple in the Foxes’ case. However, spiritualist communities still maintained their search for confirmation and solace—that life did not end after death. Your photographic practice revolves around a similar psychology, a purposeful ambiguity that could be perceived as deceptive or demonstrating the cameras ability to capture and contain spiritual realities. What can you tell me about your desire to intentionally blur the lines between these spaces?

S.T. Photographing Spiritualism presented a unique challenge—how do you photograph the invisible? Sitting in the charged séance atmospheres I encountered, I struggled with how to approach the exchange between a veiled presence and a visible body. Technical mistakes led me to explore the inherent imperfections within the photographic process. Unpredictable elements (blur, abstraction, motion, flare) seemed to insinuate, or refer to, the unseen. I began to use conventions that are considered wrong, messy, or “tricky.” I crossed the boundary of what is considered unprofessional in the practice of photography—I invited anomaly. Accident and error offered a photographic language to be translated, a set of symbols to be mined for meaning. In this play with the process, the invisible was automated. My camera rendered some striking synchronicities. The resulting images consider the conjuring power of photography itself.

I attempt to delve into the mystery of both Spiritualism and photography by constantly trying to turn one back onto the other, like a feedback loop. I purposely try to blur the line between cause and effect, to confuse the point where one technique stops and the other begins. I include pictures that use photography’s own mechanisms to question these spiritual realities—photographs that contain both mechanical and spiritual explanations, requiring an interpretation.

E.L. When you’re positioned in a ritual’s space, how do you determine the right moment to begin photographing? Do you shoot continuously or are there moments where your intuition guides your decisions? Are there moments that feel more right than others?

S.T. When I’m photographing, I try to become as much a part of the event as possible. I choose one spot and I don’t move around. My goal is always for people to forget the camera is there, or have it blend as seamlessly as possible into the event. I only shoot when the moment feels appropriate. I try not to over think anything, and try to be as present as possible while the experience is taking place.

E.L. I’m intrigued, not surprised, by how music plays a large part in creating the atmosphere when a medium is preparing for a sitting. This practice is very similar to the Shakers and their belief in mediums as instruments and their interest in trance states: singing, dancing, whirling in place, and speaking in tongues. Can you tell me how the mediums you have photographed use music? What do they listen to and what kind of devices do they use to listen? Does music or ambient sound influence how you respond to the environment as an artist?

S.T. Some physical mediums do use live drumming, but most often they curate a mix of pop songs that are played on a stereo in the séance room. Audience participation is key, and as a sitter, you may be asked to sing along at the top of your lungs. Sometimes during physical séances, participants are granted the opportunity to interact with dead celebrities, so the songs played may be related to those spirits whom the medium wishes to bring into the room for an appearance. Louie Armstrong, Freddie Mercury and Michael Jackson are among the most sought after post-death performers.

E.L. Your work pushes boundaries and stresses the importance of asking questions about anomalies in our environment and our own consciousness—to examine the possibility of the spirits ability to evolve after death. Is there a singular question that you find yourself always coming back to when you begin working on new projects?

S.T. I see my work as much about the photographic process as it is about what I am photographing. So, the big question is always how to apply the process to the situation in order to render its photographic reality in the best way. When photographing Vodou ceremonies, I found myself going back to high speed black and white photography with a flash, which is the opposite approach I used with Spiritualism. So, I’m always using the photographic process as a guide to my subject matter.

©2017 Desert Suprematism

Shannon Taggart is a photographer and independent researcher based in Brooklyn, New York. Her photographs have been exhibited and featured internationally, including within the publications TIME, New York Times Magazine, Discover and Newsweek. Her work has been recognised by Nikon, Magnum Photos and the Inge Morath Foundation, American Photography, the International Photography Awards and the Alexia Foundation for World Peace. From 2014 to 2016, she was Scholar and Artist-in-Residence at the Morbid Anatomy Museum in New York. Shannon has lectured internationally on her work.

Her monograph on Spiritualism SÉANCE: Spiritualist Ritual and the Search for Ectoplasm will be published this year. She is currently doing a pre-sale campaign for the first edition. Link to campaign – https://unbound.com/books/